There may have been no tighter nor more unlikely friendship linking ring with stage, or sport with literature for that matter, than the enduring relationship between heavyweight champion Gene Tunney and Nobel Prize-winning playwright George Bernard Shaw.

Tunney, raised on the Lower West Side where “pugnacity took precedence over romance,” and the angular, older Shaw, who was not reluctant to enter the ring as an amateur, and for whom the “raw drama of the ring in all its color, excitement and controversy” fed his imagination, were remarkably alike in spirit, curiosity and determination, both physical and intellectual.

Jay R. Tunney, writer, businessman and student of Shaw and his works, tells this remarkable and exotic story with drama, passion and grace, intimate as only a son’s remembrance can be, but always in the context of American and world history in the 1920s and ‘30s that was the stage for both Gene Tunney and G.B. Shaw.

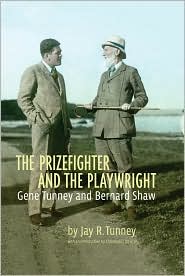

The photograph on the cover of The Prizefighter and the Playwright—the tall, muscular, firm-jawed boxer and the slender, white-bearded playwright gripping a walking stick—is a fitting visual introduction to this strange and eloquent memoir in which brains and brawn merge, perhaps as never before.

Tunney and Shaw were aware of each other at least two years before they met. Training in the Adirondacks for his first fight with Jack Dempsey, in 1926, Tunney told reporter Brian Bell he was relaxing with Samuel Butler’s memoir, The Way of All Flesh, which, he said, began with an excellent preface by George Bernard Shaw. “There is little to suggest the gladiator in this mild, quiet-spoken, blue-eyed individual,” Bell considered, “as he talks of tennis, golf, books—Wells, Tennyson and Omar Khayam are among his favorite authors.”

The revelation, which Tunney never hid, would bring mockery and teasing throughout his career from reporters who were more accustomed to Dempsey’s penchant for comic strip, and even lesser literary pursuits from the athletes they covered..

Shaw meanwhile followed the buildup to the fight from London with mounting anticipation. “Everything he remembered and read about Tunney interested him,” Jay Tunney recounts, “in no small part because the boxer seemed to bear a resemblance to his fictional hero Cashel Byron”—boxer-protagonist in an early Shaw story—“and Tunney was fighting against a man who was the personification of Cashel’s fictional opponent, the mauler Billy Paradise. Shaw told Lawrence Langner, his exclusive agent in New York, that the invincible Dempsey could be beaten by a scientific fighter.”

He was, on Sept. 23, 1926, in Philadelphia, and again by Tunney, a day less than a year later in Chicago, in the “long count” fight that is one of the most famous in boxing history. Tunney retired as undefeated heavyweight champion after beating Tom Heeney in 1928.

Jay Tunney recounts his father’s career in all of the dramatic and colorful detail that it deserves, and it is one of the ironies of life that Dempsey—loud, brash, bullish and a celebrity fit for the Golden Age of Sports—is more easily recognized today than the “scientific fighter” who beat him.

But all of that, in a sense, is only introduction to the bigger story in Jay Tunney’s view, that of the enduring friendship between the two men, and his father’s soul and humanity as a husband, parent and champion of life.

Gene Tunney married Mary “Polly” Lauder in 1928, and their relationship with each other and with G.B.S., as he is known in this part of the book, and Shaw’s wife, comprise much of the rest of this fascinating memoir.

Polly’s illness shortly after their marriage, while on the Adriatic island of Brioni, underscored the nature of the friendship between Tunney and Shaw. With Polly seemingly near death, the prizefighter and the playwright wandered one evening into Saint Rocco’s Chapel, which was built in 1504. Tunney, once an altar boy, told Shaw it had been a long time since he had been to confession or attended Mass. Jay Tunney recounts this conversation:

“You may have left the church,” Shaw said, “but the church would not leave you.”

“I am one of those people who believe in prayer,” said Gene.

“Then you must pray,” said Shaw.

Like a lot of other things in Gene Tunney’s life, he succeeded in that arena, too. Polly survived after surgery by two German doctors vacationing on the island. The operation was in the kitchen of the hotel on the island..

G.B.S. died in 1950, Gene Tunney in 1978, and his widow outlived him by 30 years.

The Prizefighter and the Playwright is packed with rare and fascinating photos and illustrations, many of them from the family collection, and concludes with an invaluable “outline of sources” by the author.